“Life is a balance between what we can control and what we cannot. I am learning to live between effort and surrender.” ~Danielle Orner

I was slumped against a wall at Oxford Circus Station early one Sunday evening when an irritated male voice suddenly barked, “MOVE!”

Moments beforehand, I had lost my vision.

Without conscious thought, I muttered, “RUDE!” and staggered off without clearly seeing where I was going.

It was only months later, on retracing my steps at Oxford Circus, that I realized I’d been blocking his view of some street art.

I’d allowed a guy to bully me out of the way while in a vulnerable state so that he could take a picture for social media.

We can never fully know what someone else is experiencing. Mental health, chronic pain, and disabilities are not always apparent. So, when we come from a place of not knowing and are patient with others by default, we open up a window of possibility that exists outside of our judgment.

Minutes prior, I’d stepped off an underground train and onto an upward escalator. A pain hit my right temple like a bullet. It took my breath away, everything went black, and I felt I might faint.

Desperately, I clung to the railing. And as the top of the escalator approached, my right foot went floppy, and my vision disappeared. I could see light and color, but the world was blurry, lacking definition.

I used what little vision I had to follow the distinctive white curve of Regent Street down to a spot where I’d arranged to meet a friend

Panic finally set in when I realized that my friend was walking toward me, and I could recognize his voice but I could not see his face at all.

We sat down in a restaurant, and a concerned waitress brought a sugary drink.

My mind went into overdrive: “Had I cycled too much? Was my blood sugar low? Had I eaten/drank enough? Given myself a stroke? Was I just stressed?”

Twenty minutes later, my vision slowly returned.

Relieved but freaked out, I asked my friend if he thought I should go to A&E (ER). He said, “Only if you think you need to.” I felt silly. Scared to take up space. Afraid of being a drama queen. I didn’t trust myself or my experience.

The opinions of others are helpful, but only you see and experience life from your own unique perspective. Learning to trust and validate our own experience first and foremost is how we step in our power.

Later I went back home but couldn’t shake it off.

The next morning, I visited my doctor, who sent me straight to A&E (ER). The hospital admitted me overnight, concerned it was a mini stroke or aneurysm. But the following morning they discharged me, citing dehydration as the cause.

One week later, I was back in A&E. More dizziness, more foot numbness, more blurred vision. A doctor described it as “classic Migraine Aura.”

My gut leapt; that didn’t feel right. “I don’t get headaches,” I protested. “I rarely take painkillers. Why so many all of a sudden?”

They seemed confident it wasn’t serious, but booked an MRI scan, just to be certain.

Twenty-five minutes of buzzing, clanking, and humming later, I glided out of an MRI scanner.

I thanked the technician. “All good?” I asked.

“It’s very clear,” she replied.

If your gut says that something is off, listen to it. A gut feeling is typically a lurch from your stomach rather than chatter from the mind.

My gut knew it wasn’t migraines; it told me so, and if I hadn’t strongly advocated for myself, then I may not have got that MRI scan.

A week later, I was back with my local doctor, experiencing vertigo and earache.

Did I have an ear infection? Was that the issue all along, some sort of horrible virus affecting my sight and balance?

The GP opened my records up on his computer and his face immediately dropped.

“Do you mind if I take a moment to read this?”

“Of course,” I said.

He composed himself but his face was ashen.

“Has anyone spoken to you about your MRI result?” he ventured at last.

I found myself detaching from reality, like I was watching a movie.

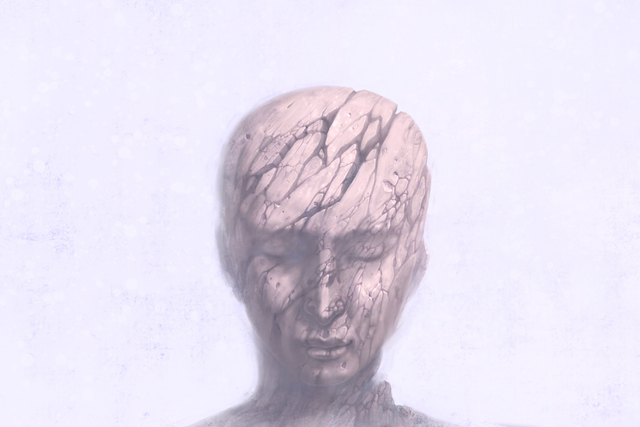

He told me that they’d found a lesion on my brain and there was a possibility of brain cancer. “I’m so sorry,” he offered finally.

I left and immediately burst into tears.

Six days I lived with the idea of having brain cancer.

Had it spread? How would they treat it? Could they treat it?

More dizziness, more vertigo ensued, and a wise friend firmly told me to go back to the emergency room and refuse to leave until I got answers.

Reluctantly, I entered A&E (ER) for the third time.

After a long wait, a neurologist sprang from nowhere, took me to a room, and showed me my MRI scan. I was shocked by the large white circle in the middle of it.

“How big is that?” I gasped.

“About the size of a pea,” the doctor said casually. “I believe it’s a colloid cyst, a rare, benign, non-cancerous tumor. It can be removed by operation, using a minimally invasive, endoscopic camera.”

Relief flowed through me. “It’s not cancer?”

After reassuring me it was not, the doctor sent me away, telling me to await further news.

Outside the hospital I hung around updating loved ones by phone. Suddenly a withheld number rang.

It was the neurologist: “I’ve spoken with neurosurgeons, and they think you should be admitted to the hospital for emergency surgery. If the cyst bursts you have one to two hours max, or that’s it.”

“Okay,” I stammered. “I’m actually still at the hospital.”

“Not this hospital,” he said. “A different one.”

A taxi ride later, it was 5 p.m., and I was in an emergency room for the second time that day and fourth time that month. Despite the chaos around me, I eventually curled up and got a little sleep.

Suddenly it was 3.30 a.m. and I was still in A&E. Staff rushed in, grabbed my bed, and hurtled me through corridors. Bright lights from London’s skyscrapers flashed past windows, everything surreal and movie-like again

The next day, surgeons explained that they wouldn’t be sure that they could reach the tumor until they operated, and there were four different options for surgery, ranging from a minimal endoscopic camera through to opening my skull up with major surgery.

I hoped and prayed for endoscopy but wouldn’t know the outcome until I woke up.

The operation was planned for 8 a.m. the following morning. I said an emotional goodnight to my sister. Suddenly a lady interrupted us and said, “I hope you don’t mind me saying, but I saw you earlier and you don’t look sick enough to be on this ward.”

And there it was—the trigger again, the gift, the insight, the lightbulb moment:

“Despite how bad I feel on the inside, I don’t look ill enough to have a brain tumor.”

I didn’t look ill enough to the guy at Oxford Circus taking a selfie.

I didn’t look ill enough to my friend.

I didn’t look ill enough to the doctors who turned me away initially.

And now I didn’t look ill enough for this lady’s expectations of who should be in a head trauma ward.

I breathed into that pain. Into the feeling of not being seen. Of not being heard. Of not being validated. Of feeling like a fraud, an imposter. Of not deserving to take up space. Of not trusting my experience.

And when I found my center, I quietly replied, “Actually, I’m having surgery to remove a brain tumor tomorrow morning.”

Her face fell, then she wished me luck and moved on.

When we are triggered, it shows us what needs to heal.

It was me who felt unworthy of taking up space. It was me who felt like a fraud. She was simply my mirror. It’s up to me to heal those aspects within myself and to believe that I’m worthy of taking up space—and to then take it.

The next morning, my operation got pushed back. It was a major trauma hospital, and bigger emergencies took precedent. I engaged in mindfulness to stay centered.

I did an hour of breathwork to calm my nervous system. I listened to uplifting music to raise my vibration. I watched emotionally safe movies to collect warm, fuzzy vibes. I drew on my iPad and alchemized my head tumor into a cute pea cartoon character—benign, polite, and cute, not threatening at all.

A porter arrived at 5.30 p.m. and whisked me away for surgery. After weeks of surrendering to the unknown, it was now time for the ultimate surrender of any illusion of control. I took a deep breath as anesthetic filled my veins.

We can’t always control what happens to us or the outcome. We can only control what happens inside of us and how we choose to show up. We take our power back when we lean into the unknown and surrender. When we resist our current reality, we suffer more.

I woke up two hours later and got sick.

My brain was rebalancing after months of increased head pressure. Clutching a blue plastic bag, I looked up to see one of London’s best neurosurgeons waving cheerfully at me. “Your operation is over. We used an endoscope. Minimal invasion. We think we got it all, and it’s not likely to come back.”

Relief, nausea, and gratitude flowed in abundance.

I dozed a little while morphine played tricks on my mind. Delicious little dreams filled my head, and I saw the world as one big, animated garden with flowers as cartoon characters.

I giggled at the thought of plants acting as humans do and imagined an aggressive rose bush declaring war on all of the other plants and throwing bombs. It seemed ridiculous. Humans should be more like flowers, I thought—less ego, just growing, flourishing, blooming.

I enjoyed this magical trip a little longer, a welcome respite from the hell of the last month, and eventually they wheeled me back to the ward.

I arrived in time to see the sun setting across London from the twelfth floor.

It was magnificent. Its beauty, color, and intensity moved my weary body to tears.

A nurse came to check that I was okay, and I assured her that I was crying happy tears.

I silently watched the sun as it made its final slip over the horizon, safe in the knowledge that I’d survived another day.

Ruth AJ Wilson is a cartoonist and the founder of Littlest Nopes, a social media space for mental health illustrations and animations. She’s also a creative life coach, helping others to step into their power and to follow their soul’s mission.